Nietzsche's Rehab: G-d is d--d. And we k----d him!

On the occasion of (non-Orthodox Christian) Easter

Note: I’ll strive to start every month with a post based on Nietzsche’s writing. Time will tell how long that would last 😌 Regardless, I hope these posts will make someone reconsider FN’s image in their mind✨

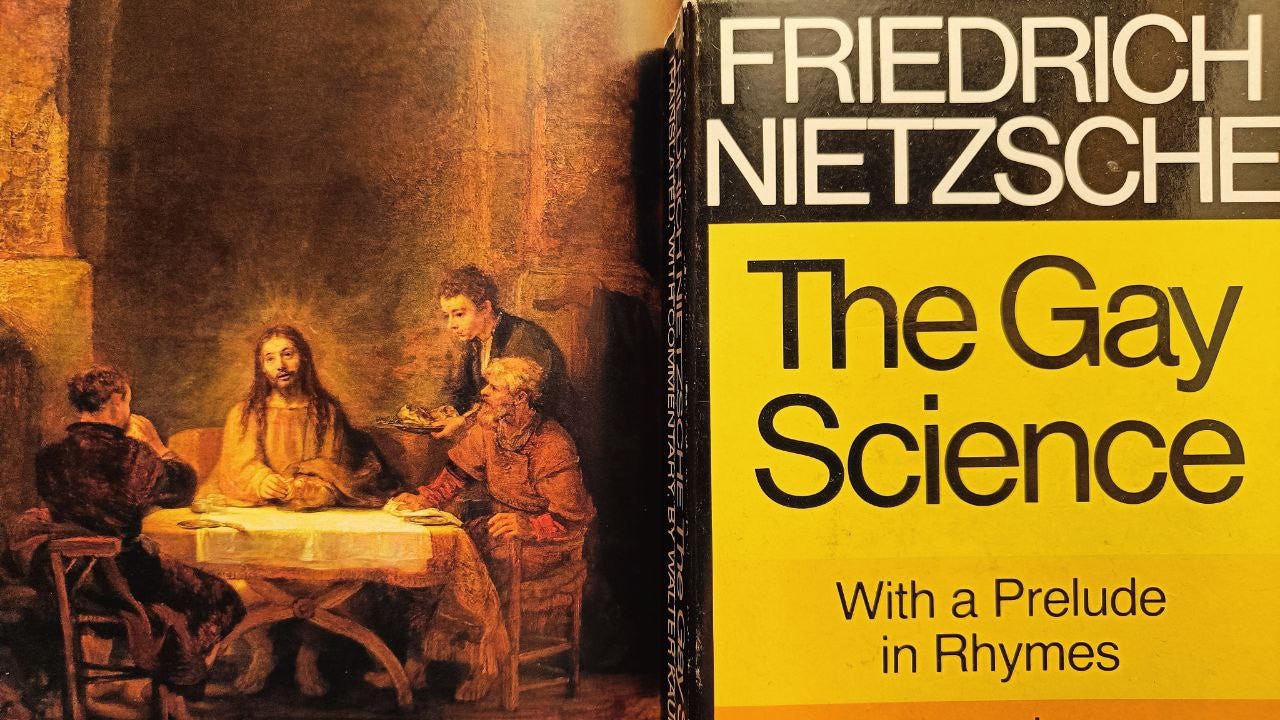

Arguably, if you hear “Nietzsche“, one of your immediate associations with him stems from this passage, which comes from The Gay Science but was also later reworked in Thus Spoke Zarathustra:

125. The madman.—Have you not heard of that madman who lit a lantern in the bright morning hours, ran to the market place, and cried incessantly: “I seek God! I seek God!“ —As many of those who did not believe in God were standing around just then, he provoked much laughter. Has he got lost? asked one. Did he lose his way like a child? asked another. Or is he hiding? Is he afraid of us? Has he gone on a voyage? emigrated? —Thus they yelled and laughed.

The madman jumped into their midst and pierced them with his eyes. “Whither is God?“ he cried; “I will tell you. We have killed him—you and I. All of us are his murderers. But how did we do this? How could we drink up the sea? Who gave us the sponge to wipe away the entire horizon? What were we doing when we unchained this earth from its sun? Whither is it moving now? Whither are we moving? Away from all suns? Are we not plunging continually? Backward, sideward, forward, in all directions? Is there still any up or down? Are we not straying as through an infinite nothing? Do we not feel the breath of empty space? Has it not become colder? Is not night continually closing in on us? Do we not need to light lanterns in the morning? Do we hear nothing as yet of the noise of the gravediggers who are burying God? Do we smell nothing as yet of the divine decomposition? Gods, too, decompose. God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him.

“How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers? What was holiest and mightiest of all that the world has yet owned has bled to death under our knives: who will wipe this blood off us? What water is there for us to clean ourselves? What festivals of atonement, what sacred games shall we have to invent? Is not the greatness of this deed too great for us? Must we ourselves not become gods simply to appear worthy of it? There has never been a greater deed; and whoever is born after us—for the sake of this deed he will belong to a higher history than all history hitherto.”

Here the madman fell silent and looked again at his listeners; and they, too, were silent and stared at him in astonishment. At last he threw his lantern on the ground, and it broke into pieces and went out. “I have come too early,“ he said then; “my time is not yet. This tremendous event is still on its way, still wandering; it has not yet reached the ears of men. Lighting and thunder require time; the light of the stars requires time; deeds, though done, still require time to be seen and heard. This deed is still more distant from them than the most distant stars—and yet they have done it themselves.“

It has been related further that on the same day the madman forced his way into several churches and there struck up his requiem aeternam deo. Led out and called to account, he is said always to have replied nothing but: “What after all are these churches now if they are not the tombs and sepulchers of God?“

Which actually isn’t the first passage to make the infamous statement. That first one opens Book Three, to which The Madman belongs, and goes like this:

108. New struggles.—After Buddha was dead, his shadow was still shown for centuries in a cave—a tremendous, gruesome shadow. God is dead; but given the way of men, there may still be caves for thousands of years in which his shadow will be shown. —And we—we still have to vanquish his shadow, too.

From then on the thought is being developed down to passage 125, where it culminates in a rather dramatic fashion.

To reiterate, I’m no Nietzsche (or philosophy in general, for that matter) scholar as much as a casual enjoyer. FN’s writings resonate with me and work as a wonderful springboard for pondering about life. And FN is particularly good for it thanks to his counter-culture thinking, his tendency to dissect without moral qualms and yet to remain oddly positive. Nothing short of inspiring.

All of that is to say that my goal here is not to write a thesis but to show how relevant FN might to our everyday life and how spot on his observations were (not all of them though; plus his proposed solutions sometimes fall short of his criticism. But then, it’s always easier to point out what’s wrong than to say how to fix it.)

Now, there is a book I read last year called After Virtue by Alasdair MacIntyre, which I first found in e-book format but then asked for the physical copy as a birthday gift — that’s how I liked it. That one was written by a scholar, and it was an enriching, even if immensely humbling, experience to spend a few weeks in such a company. The main thesis — or my main takeaway, for that matter — was that the so called Enlightenment project was a failure. The aim of this project was to give rational basis for morality/ethics in the absence of God, which ultimately split philosophy into so many branches that we are now deadlocked into the sort of arguments, in which both parties hold rationally valid arguments which stem from contradictory premises, and so are by their nature unresolvable (think debate on abortions: your stance depends on whose “rights“ you’re protecting—the woman’s or the fetus’).

MacIntyre’s argument is that Enlightenment cut off an essential part of a scheme that in previous epochs made morality functional: on the one hand you have man-as-he-is, on the other you have man-as-he-could-be-when-he-reached-his-potential, and to get from point A to point B you need morality, the latter being essentially a practical tool, something very concrete, and not abstract. There were no universally applicable “rights“, there were rules (and allegiances) that guided you in various situations. And their clash would make Greek tragedies of the sort where the hero has to make a choice, say, between protecting his friend or his homeland. (Which led me to thinking that Steve Rogers/Captain America is a classical hero, whereas Tony Stark/Iron Man is a Christian one.)

And, as MacIntyre underscores, the humanity welcomed the paradigm shift, in which point B was dropped because, essentially, it was too restrictive. Who’s to tell me what I should make of my life? I have my feelings! I have my desires! I have ME! While previously it would’ve been nigh a death sentence to be on your own (see the origins of the concept of ostracism), now it was seen as something worth celebrating — a liberation. But the caveat to this is that morality was left dangling in the air. Enlightenment thinkers apparently did feel uncomfortable with ditching it altogether, because there was something inexplicably wrong about it, and so each turned to various sorts of mental gymnastics, like “ethics are here to restrain man who is too wild and destructive by nature“ and so on. The end result of all this, however, was that now morality (which, by the way, did not exist as a concept back in the classical days) is purely relativistic.

Which naturally leads to conflict. Especially, to use FN’s comparison, because some seem to have decided they themselves are gods.

But that’s an obvious point. A less obvious one echoes Nietzsche (in fact, MacIntyre recalls him, too, and appreciates his insights into critiquing the state of affairs): without that framework, which was largely based on divinity, whither are we moving? And by that I mean each of us individually, first and foremost. In the world which tells you to “just be yourself“, which is of itself nonsensical and was unsurprisingly coopted by capitalism into another stream of revenue, how are you to conduct your life and not go exasperated and desperate? (Let’s put aside the reality of a thousand and one socio-economic constraints on your choice for a moment.)

Doing away with God was seen as an act of breaking the chains, but it feels like it’s done more harm than good to us mentally and culturally. Yet what FN pointed out to 150 years ago, I think, still stands: we still didn’t put the finger on the problem, in part because it’s something so awfully immense and beyond comprehension. Of course, there’re still full on cults and other deeply devotional Christians (the US as a prime first-world example and an odd outlier), but by their nature they belong to Passage 108. They’re worshipping shadows.

The truth is, that the deed was done, God is not coming back, and that leaves us with the question: What do we do now?

In conclusion to 113 Nietzsche writes:

And even now the time seems remote when artistic energies and the practical wisdom of life will join with the scientific thinking to form a higher organic system in relation to which scholars, physicians, artists, and legislators—as we know them in present—would have too look like paltry relics of ancient times.

— which is a vague enough recipe. But that’s the thing: we need yet another paradigm shift of sorts to get out of our present conundrum. We cannot roll our civilization back (as MacIntyre kinda suggests in his book that we should try), it’s gone for good. Although I do believe that we can bear Christianity in mind as a once-functional framework, to draw some inspiration as to what effects we want to achieve (mainly, some spiritual self-anchoring). At the very same time, FN is certainly not willing to give up on individuality. Maybe in our curse lies our salvation.

I hope no one here truly expects a little me to uncover a solution to this. FN didn’t have one laid out either. I don’t think a single mind is capable of this.

But it doesn’t mean we shouldn’t ponder. That’s what I hope to be doing in this blog of mine anyway: to bring together different threads and see what can be woven with them.

Happy Easter to all those celebrating!