Nietzsche's Rehab: Life's Narratives

With a touch of Alfred Adler by way of "The Courage to be Disliked"

Note: My pledge to start every month with a post based on Nietzsche’s writing might have had a hiccup but we’re back on air 😌 I hope these posts will make someone reconsider FN’s image in their mind✨

44. Supposed motives.—Important as it may be to know the motives that actually prompted human conduct so far, it may be even more essential to know the fictitious and fanciful motives to which men ascribed their conduct. For their inner happiness and misery has come to men depending on their faith in this or that motive—not by virtue of the actual motives. The latter are of second-order interest.

Some — a lot — of Friedrich Nietzsche’s passages would make you believe he should be studied as a psychologist, not just as a philosopher.

And I must admit that I struggle with this specific passage, however short it is. I feel it in my gut that there is still something that escapes me about it, I still didn’t experience this “oh, right!“ moment, that clicking sound that goes off when the detail passes neatly and completely into its slot.

So I’ll just set it aside and talk about a book that this passage reminded me of, a book that I read last winter: The Courage To Be Disliked by Ichiro Kishimi and Fumitake Koga.

The book is practically an explanation of the approach to psychology by Alfred Adler, who, according to my boyfriend that studies psychiatry, is more of a side note these days, in comparison to, say, Freud or Jung. The book itself is extremely readable, deceptively so, because it is formatted in a classical manner as a dialogue between Philosopher and Youth, but then the text is so dense with thoughts that I must have highlighted a good half of it.

And for the purposes of this post I would set aside that part of the book that deals closely with interpersonal relationships, purely for the sake of space and not because it is uninteresting — quite on the contrary. Go check it out for yourselves.

But FN bids us to talk about personal narratives, and that’s what I’ll try to take from (hopefully truthful) retelling of Adler’s approach, since I found it fascinating and practical.

First things first: Adler denies the concept of trauma (popularized by Freud), at least partly because he views it as deterministic, meaning, that if you experienced some traumatizing effect, your entire life is going to be bent by it and you’d be ever unhappy (until Freud treats you).

What Adler insists on instead, is that the primary driver of life/fate/you-pick is personal choice, and that is only possible if you drop the tendency — that human, all-too-human tendency! — to make a narrative out of you life, with inescapable causality and “sense of dramatic development“. What Adler, as quoted in the book, suggests is the following:

No experience is itself a cause of our success or failure. We do not suffer from the shock of our experiences—the so-called trauma—but instead we make out of them whatever suits our purposes. We are not determined by our experiences, but the meaning we give them is self-determining.

And another crucial tidbit:

The important thing is not what one is born with but what use one makes of that equipment.

I guess, the thing I viscerally dislike about the entire trauma discourse is how past-oriented that is and how bent it is on the idea that you’re stuck forever until you “heal“. Actually, the vocabulary rubs me the wrong way, too. What kind of trauma is it that it’s now evidently chronic, since you’ve been running around with it for years?

Are you sure you’re not just using some past event as an excuse for being miserable today? And, for what’s worse, blaming your parents for it, who, hey, probably tried their best? It’s not like they got a neat manual on how to raise a human while also handling themselves, their jobs and other relationships, right?

(If we should make bodily metaphors, I’d rather build mine around scars: you got an injury, because life happened, it’s relatively quickly healed, you move on, with the place of injury stronger now.)

This is what resonated with me about Adler’s ideas. That all those narratives are essentially a rationalization of why we can’t be happy here and now, why we dislike ourselves and, by extension, why we can’t build good relationships (if we even decide we deserve these). “I’ll find happiness when I am entirely healed“ — if you ask me, that’s just bloody convenient.

What Adler is saying is actually happening, is that you, okay, some other person decided to be unhappy. Not necessarily consciously. It just paid off once back in the day in some very specific context, and the brain, naturally, memorized it as a valid method of achieving a desired outcome. And here we are. With the exception of that particular event, your circumstances as such have nothing to do with it. Nada. Nichts.

In Adlerian psychology (and here’s another reminder that I’m going off of a single book that’s retelling his ideas — but it’s so cohesive, that I’m comfortable sticking to it), there is a concept called “lifestyle“, which can be called a worldview: how you see the world and how you see yourself. For example, it might sound like “I’m a pessimist“ or “I’m socially awkward“. But the thing is, you just chose it once. And, the logic says, you can choose something else at some other point (like, now, anyone?). The catch, I’d say, is in our wiring: our brains feel uncomfortable at the sight of change because it brings in so much more newness and, with it, uncertainty. Naturally, it’d prefer inertia and sticking to the old and familiar. Less work, really.

YOUTH: One wants to change, but changing is scary?

PHILOSOPHER: When we try to change our lifestyles, we put our great courage to the test.

Here’s an example used in the book: say we have a man, let’s call him Joe, who all his life wanted to be a fiction writer. But he didn’t write anything. He says his jobs keeps him too busy. His family, too. There’s just not enough time to write even a short story and submit it for an award.

PHILOSOPHER: But is that the real reason? No! It’s actually that he wants to leave the possibility of “I can do if I try“ open, by not committing to anything. He doesn’t want to expose his work to criticism, and he certainly doesn’t want to face the reality that he might produce an inferior piece of writing and face rejection. He wants to live inside that realm of possibilities.

[…]

He should just enter his writing for an award, and if he gets rejected, so be it. If he did, he might grow, or discover that he should pursue something different. Either way, he would be able to move on. That is what changing your current lifestyle is about.

See? All those narratives are just so convenient.

And this fear of rejection, this fear of getting hurt in your relationships with other people is the driver behind you disliking yourself. One’s focus on one’s shortcomings neatly explains why one should stay away from other people as much as possible, so that one doesn’t bother them with his/her nastiness, when in fact one avoids people to not get hurt oneself.

YOUTH: I have resolved to not start liking myself?

PHILOSOPHER: That’s right. To you, not liking yourself is a virtue.

I find this point extremely relevant for our current culture which, as I think I’ve already mentioned some other place, seems to be hellbent on eradicating any possible friction in life it can reach. A good example would be a self-checkout at the supermarket (of which I am myself an avid user): not only you don’t have to ask a real person to get you this and that, and weigh it and pack it — you also don’t need to interact with anyone while paying. Of course, one might say that it saves everyone time. Sure. But at what cost? Do you really need that time that badly? What for?

This drive for efficiency leads to sterility, and that’s what even more scary to me. Which is why I’m consciously trying to get that human friction back into my life. I’m even thinking longingly of those little markets, where I was tagging behind my mom while she was comparing the prices at different stalls to get the best deal, and where you could find everything, from pasta to DVDs, from fish to panties, all in one place. And no self-checkout. I now wish I had a bit more time to grow up in that environment to feel natural in it. Now I have to gather my courage and learn. Which isn’t a bad thing, it’s just wild to me how we lost it and celebrated it. Now look at all this anxiety that’s only keeps spreading further like a cancerous growth.

PHILOSOPHER: Before being concerned with what others think of me, I want to follow through with my own being. That is to say, I want to live in freedom.

[…]

Not wanting to be disliked is probably my task [one might rephrase it as responsibility], but whether so-and-so dislikes me is the other person’s task.

[…]

The courage to be happy also includes the courage to be disliked.

I think that’s what I deeply admire — and envy — about my self defense instructor: he very obviously likes himself. Even when telling a story about how he got so drunk that he doesn’t remember how he got home and how he smashed his face so that some skin on the bridge of his nose tore open. Like, he’s no gentleman or a nice guy but he’s just a magnet for people, and my educated bet is that that’s due to this superpower of his. It gives him so much energy, he exudes it, and hey, whoever has so much energy must know where it’s source is, right? And so it’s very natural for other people to follow that person, if only due to that implied promise of drinking from that source, too.

Philosopher, when being asked by Youth if he likes himself, shortcomings and all, says that he at least doesn’t dislike himself. And even that seems a lot. I, for my part, certainly struggle with self-perception. Even from other people’s positive responses I’m often left perplexed as to what they based them on. Like, they’d say I’m smart, I’d think: reading is easy. They’d say I’m reliable, I’d think I’m bloody lazy, what do you mean.

Maybe that focus on the negative is also because it points at issues to work on. Kind of an area of improvement. A to-do list. But something just overkills it, throwing all the good stuff out of the window. And then come moments when you yourself get shocked at how far you’ve come and how competent you got at something. “Who? ME?! You must be joking. Okay, come on, what’s the catch?“

Except there’s none.

What I’m also heavily reminded of while writing this piece is William James and his Pragmatism. In his book called, well, Pragmatism, James gives us this neat mantra:

Truth happens to an idea.

To put it very crudely, if you believe in God and it helps you in your life, then it’s the truth. Or, if you don’t believe in trauma, you don’t spend time and money on therapy, coming up with stories about you childhood (because who remembers their childhood clearly enough to judge their parents’ behaviour??), you just live your life, and hopefully learn to avoid being a dick, simply because it’s generally a bad strategy in life (unless you’re Putin, but life be like that sometimes. Besides, his story hasn’t had an end yet).

So, going back to Nietzsche’s passage, I guess the first order narratives he talks about are Adler’s lifestyles? And the second order ones are those that Adler perceives as the “real“ motives (fear, primarily)? If so, it’s so interesting to me that FN dismisses the underlying ones as less relevant. That’s what I still haven’t worked out about it. Understanding him is very much an ongoing process. Doesn’t make him any less inspirational though.

And I really should read Adler. Or at the very least reread The Courage to be Disliked. It indeed felt like one of those books that you’d refer to continuously (their number on my list has been growing in the past year, and that’s annoying :D).

That insistence that the past doesn’t really exist, there’s only today and only what you have today matters, and what you decide to do with it — it’s so exhilarating. Liberating.

I’m just left there waiting for it to finally click in me, regarding my own lifestyle, but I also wonder if this is indeed something that happens overnight? Or maybe there is some cumulative effect at play?

There’s only one way to find out. To wait and see.

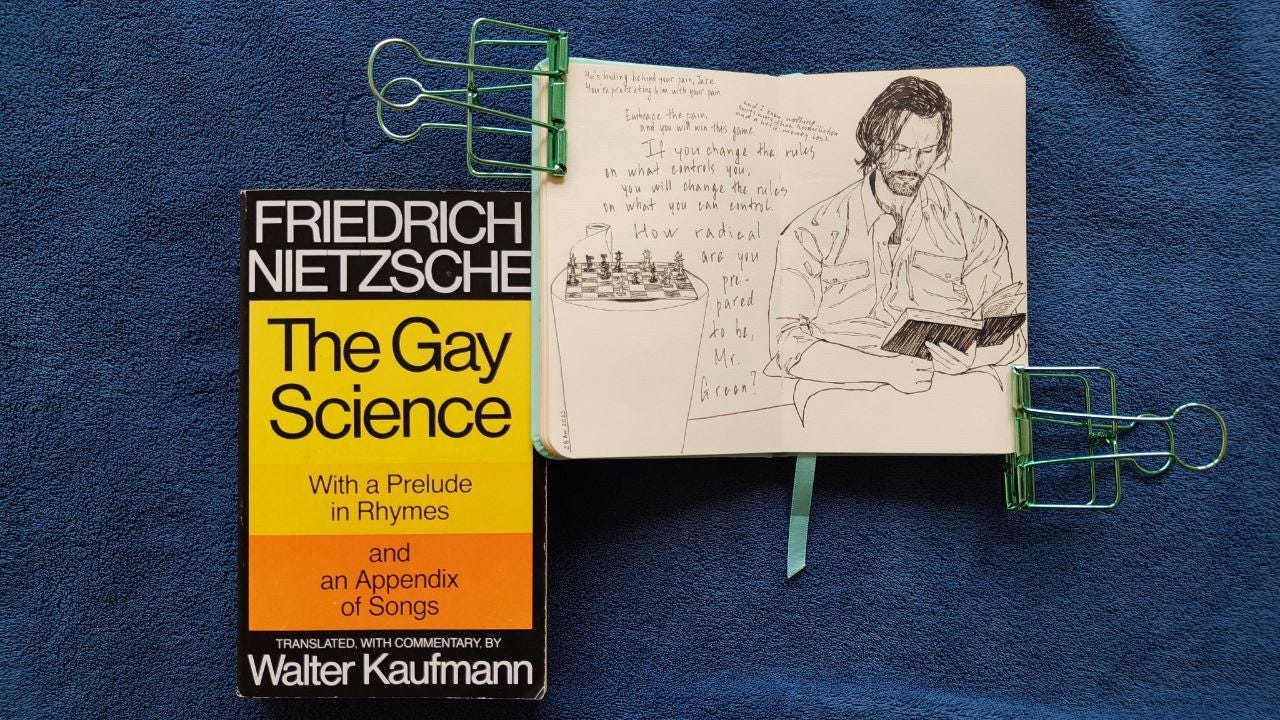

P.S.: The sketch on the image at the top is based on Guy Ritchie’s Revolver, starring Jason Statham with a head full of hair! A mesmerizing movie about ego death.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fzp7iCaWNvE

I'd say childhood trauma is more something that distorts the emotions, causing changes to personality that are difficult to trace and to resolve. The individual's decision to act in one way or another based on their trauma narrative is secondary. I agree, and it's a widely held view, FKN is a far better psychologist than he is a philosopher. His eternal recurrence is almost cosmology. And when he says things like, 'there's no such thing as cause and effect, only events...' you might choke on your soup! Of course' he's right when he says that, but it doesn't get us anywhere philosophically.

I'd venture to say everyone has some amount of trauma in early childhood, if only because our development takes place in a fully-formed and complex world. The trauma that happens a little later, when we are moving out of infancy into youth and beyond has to be more concrete. Samuel Beckett, 'every day deforms and is forgotten' is another gem!

Well done for caring!